In a new mini-series exploring why specialty chains keep failing, we start by identifying the hurdles that must be surmounted when expanding from one shop to two.

Get the latest Audio Articles by subscribing wherever you get podcasts

The Gentlemen Baristas, a London-based specialty coffee chain, recently entered administration. With uncertainty over the company’s ability to pay its bills, management appointed an external insolvency practitioner to identify a path forward. A new investor has been found who has plans to restructure the business. It’s clearly a challenging time for the owners, management and staff.

A string of entrepreneurs have now attempted to build a specialty coffee chain. Some have grown to more than five sites, with a handful expanding to over a dozen locations. However, the track record isn’t good. To date, there have been a string of failures and no clear successes. Over the past decade London has witnessed the collapse or retrenchment of Taylor Street Baristas, Timberyard, Department of Coffee, Harris + Hoole, Over Under, Espresso Room, Notes and others. The Gentlemen Baristas’ situation is far from unique.

Considering the track record, it is timely to consider why these entrepreneurs failed. United Baristas sees this question as more than tittle-tattle, it’s essential. If the entrepreneurs had a good strategy but executed it poorly, their experience provides little instruction outside of identifying potholes for others to avoid. However, and more likely, if the business strategies fell short, these experiences are highly instructive. Together these entrepreneurs’ stories have something interesting to say about the structure of the specialty coffee industry.

A growing coffee shop business has multiple moving parts. Leases are to be agreed, an attractive proposition developed, operational capacity built and a team recruited, trained and managed. To give each aspect sufficient consideration, we unpack our analysis over three articles in a mini series. This article identifies the challenges facing specialty chains by exploring the hurdles that founders must surmount when expanding from one site to two. The second article explores how these challenges combine to create a profitability chasm during the next stage of a chains’ growth. The final article compiles founders’ tips for scaling and proposes components of a potentially successful strategy.

Scaling speciality shops is (probably) not worth it

Scaling a quality, specialty coffee chain is surprisingly complex. Our view is the challenges are systemic and difficult. In fact so difficult they’re almost impossible to overcome. Furthermore, even if a specialty coffee shop chain can scale to profitability, it remains doubtful that the rewards would ever justify the investment.

We have an inside track on this discussion. Between 2010 and 2015, before founding United Baristas, Tim Ridley founded and grew a specialty coffee shop business to seven sites. He was amongst the first to scale specialty shops, with the distinctive twist that each site was individually branded. His experience and insight forms the basis of this analysis, but many other people have contributed ideas and expertise. We’ve spoken to around a dozen entrepreneurs who played instrumental roles in some of the United Kingdom’s best-known specialty coffee companies. Each generously shared their experience and insight on the condition of anonymity.

Amongst these entrepreneurs, there was common recognition of the challenges and a similar estimation of the degree of difficulty. However, some still see potential routes to success. For the sake of completeness, and at the risk of complicating our central theme, this series also communicates their tips when appropriate. We think you should embrace these nuances. After all, as this series makes clear, building a specialty coffee shop chain is a complicated business.

Amongst companies that are now defunct, some entrepreneurs underestimated headquarters costs as they grew, others were confronted by external events at critical moments, and a number had unprofitable sites drag the business down. Their central assessment is that their business ran out of money before achieving sufficient scale to be stable and profitable. The majority of these founders believe, and some with good cause, that their strategy was sufficiently strong, but they faced additional challenges, made regrettable choices or got unlucky.

While these factors clearly played a critical part in their individual stories, a narrow analysis risks overlooking the broader trends and industry-level factors. A central reason for publishing this series now is we think it’s timely to amalgamate their experiences to identify common themes. By taking a wider view, it is possible to understand how the current structure of the coffee industry stacks the odds against entrepreneurs from the outset.

But don’t be misled by the headline analysis. United Baristas thinks the industry’s future is bright. Rather than a handful of businesses dominating the sector, the industry is likely to be comprised of thousands of independent businesses each viably serving a niche of customers. As well as being more probable, this outcome is better for almost everyone from crop to cup. A community of small businesses may be both a defining quality of specialty coffee and a reason for its continued success.

To understand why scaling a specialty coffee business is both attractive and tricky, let’s start with founders’ motives.

The profit motive at work

It almost goes without saying that the primary goal of founding a specialty coffee shop chain is to make money. The plan is to build a profitable business and sell it to a new owner. This blueprint is used by entrepreneurs in many industries. However, in specialty coffee, this approach, ironically, puts entrepreneurs at a disadvantage.

Investors are often drawn to specialty coffee’s high gross profit margin. This is the amount earned, expressed as a percentage, on the retail price of a cup of coffee minus tax, beans, milk and (depending on your accountant) the paper cup. A cup of specialty coffee typically yields a high 80% gross profit margin. There are many other costs involved with making a cup of coffee, including people, rent, rates, electricity and maintenance. Many coffee businesses have net profit margins, that is profit after all expenses, of just a couple of percent. With such low profit margins, most owners appreciate that selling cups of coffee is not a quick way to get rich.

For many industry outsiders, there’s an instinct that it must be poor cost control that erodes profits. A number of people with corporate backgrounds have entered the industry with a view to bring stronger financial controls to an artisanal company. But multiple times, their belief has proven to be misplaced and has tripped them up. Another recurring theme across this series is that market forces are better at predicting success than visionary founders, MBA-level skills or even deep pockets.

Other people start a coffee business because they love the beverage and enjoy their work. Often they have strong coffee experience and may have fewer options to work in other industries. Many of these people are willing to accept smaller profits than their investor-backed competitors. The successful ones are often thrifty and have lower commercial aspirations. This means the competent founder is more likely to achieve a satisfactory business performance than the entrepreneur.

As a result, the profit of coffee shops is a contemporary take on Ricardian rent. The profitability of prime shops diminishes to equal the income available from the least viable local premises. As we shall explore in the next article, it’s not just rent-seeking landlords that curtail profits, it’s also price-sensitive consumers.

But before we get there, it’s important to first appreciate that initial success seldom scales smoothly.

Identifying product-market fit

After a few drinks, many multi-site founders reveal that their first shop was one of the most successful. And after a few more, they may even rue that subsequent sites failed to live up to expectation.

Obviously, there’s selection bias at work. It’s founders with a successful first site that have opportunity to expand. But first sites often benefit from advantages that are difficult for first-time founders to appreciate. Specifically, when inexperienced founders look for their first location they often only commit to a lease after dismissing multiple potential premises. They finally find the confidence to proceed when a site has a significant margin of safety. The buffer is typically some combination of an advantageous position, favourable rent, an accommodating landlord and a vibrant neighbourhood.

Many founders develop innovative concepts based on their personal preferences and the market has been shown to support a wide array of propositions. Some formats, such as espresso bars, focus on takeaway; many cafés also specialise in food ; and other concepts combine a retail offer with coffee.

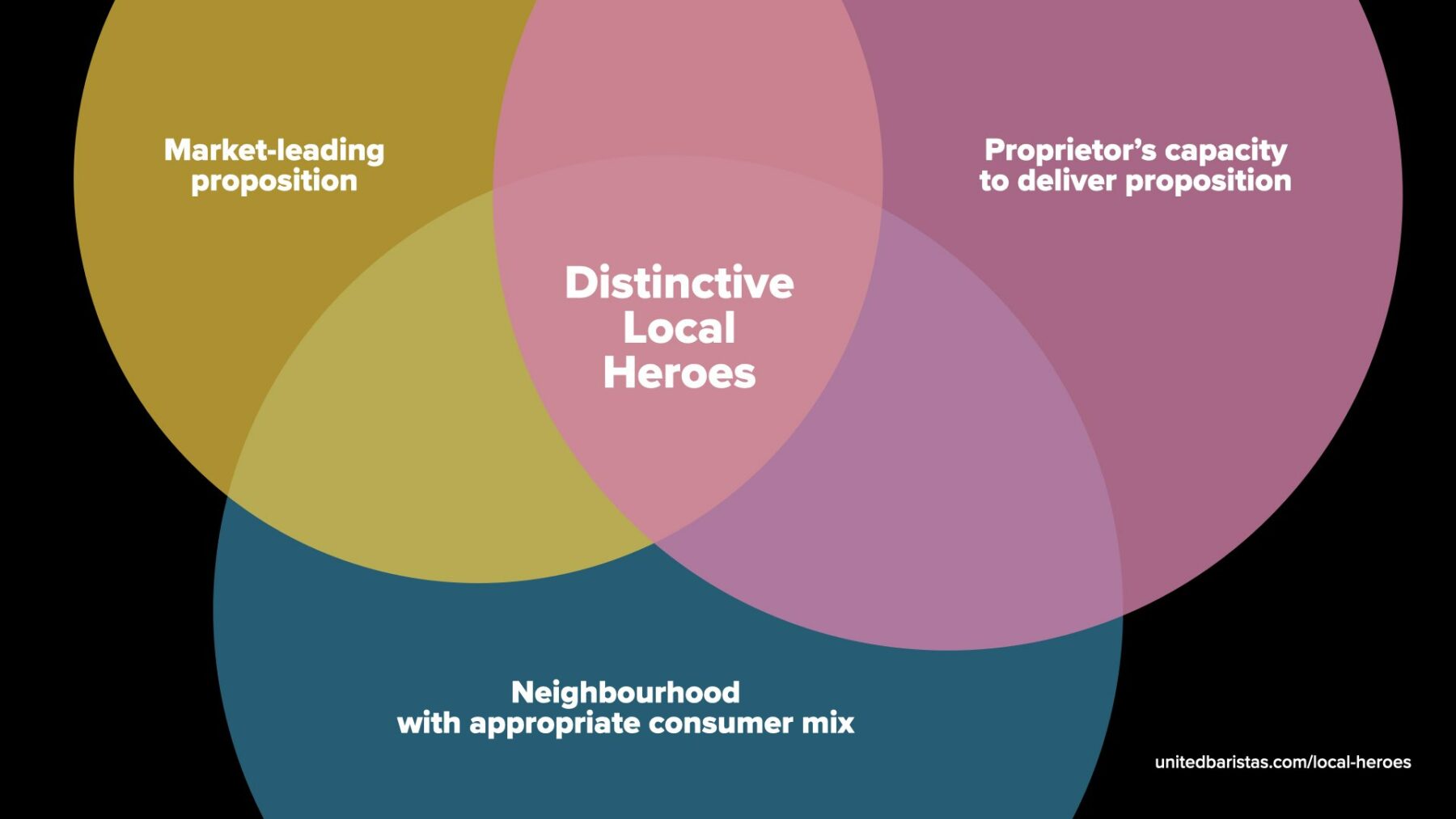

Whatever the specific proposition, all successful sites hit a sweet-spot to combine a market-leading proposition with a proprietor’s capacity to deliver that proposition. Additionally, the business must operate in a neighbourhood with a sufficient number of consumers who find the proposition attractive. Another recurring theme is that all successful specialty coffee shops are distinctive local heroes. Successful founders often have invested considerable time developing their market-leading proposition to stack the odds in their favour.

If this first shop is successful, many founders then find themselves in a confluence of circumstance. As the shop matures it no longer demands all their attention. Profitability is adequate, but not excellent. Almost inevitably, the realisation that a business twice the size would produce a healthy profit makes opening a second shop an attractive next step.

Hitting the bullseye, again

Second sites are akin to an artist’s tricky second album. Music producers advise artists to create a record that is appreciably similar to their first album to avoid isolating their hard-won fan base. Coffee shop proprietors often approach their second site with the mentality of duplicating their first shop but, unlike the musician, they have no option but to build a new customer base, largely from scratch.

For a second site to be successful, it too must identify the sweet spot between a viable proposition, operational capacity and the right neighbourhood. This requires the customer mix at the new location either to be very similar to the first shop or the proposition to be revised to reflect the neighbourhood.

These factors should be immediately apparent, however it’s often difficult for proprietors to simultaneously stay true to their vision and evolve the concept to meet the aspirations of consumers. More typically, they copy and paste the first site’s format into a neighbourhood where it risks having less resonance. Or in other cases they pivot wildly into a new proposition that lacks authenticity or is more operationally challenging.

In theory, the two sites could have completely different propositions. But in practice, enduring two-site coffee businesses almost always have near identical propositions in both sites and both neighbourhoods have similar customer profiles.

Set yourself up for success

If you are considering growing from one site to two, here are several additional tips gleaned from successful entrepreneurs.

Avoid being trapped in a commercially marginal site out of a desire to move quickly. With a stronger understanding of your business model, it’s possible to accept higher rent, tackle a trickier footprint or take a gamble on an up-and-coming location. Don’t let haste override your prudence. Proceed with as much care as your first site and consider how the neighbourhood and your proposition sync.

It’s a truism to say that this is the only time the business will double in size with a single step. The implication being that it is the crux in the life of the business. In the next article we explain there are, in fact, more complex and challenging moments to come. A good, competent operator who draws on their experience can often readily take on the demands of a second site. But remember to retain the utmost consideration for your customers.

There is a difficult choice to be made whether to staff the new site with a fresh team or to split your existing team. Many experienced operators prefer to seed new sites with their culture and processes by installing a manager, assistant manager and key barista who have been in the business for a while. This prudent approach adds additional cost as it means being overweight with staff at your first site in the lead up to opening your second shop.

Finally, don’t budget on significant cost savings across the shops. In practice your new sales volumes are unlikely to unlock significant margin. And, in fact, the company will also have to bear new costs such as inter-site meetings and transporting items between locations.

Small can be beautiful

Establishing a one or two site coffee business is a serious achievement. It takes thoughtful consideration, hard work and care managing risk. There are now thousands of small coffee businesses successfully serving coffee to happy customers. And these companies are the heart and soul of the coffee community. Collectively, they have greater sales than the specialty chains and are often the originator of trends. United Baristas thinks the industry should better appreciate their contribution and celebrate their success. If you’ve played a role building one of these businesses, we are genuinely happy for you. Well done.

As well as shining a spotlight on coffee’s success stories, our agenda is to change the narrative around scaling specialty coffee. An updated perspective better equips operators to build viable businesses, plus it also better predicts the coffee shop businesses that will work, as well as those that won’t.

In the next article we explore how market forces and events conspire against entrepreneurs to further expand their companies. Future growth isn’t linear and many coffee businesses fall into a profitability chasm. When armed with these insights it’s much easier to understand why The Gentlemen Baristas failed.

Give Coffee If you found this article useful, show your appreciation

Give Coffee If you found this article useful, show your appreciation